From phonographs to mobile phones: the British Library’s Season of Sound explores 140 years of recorded audio

From the early days of audio right through to the digital age, the British Library’s exhibition runs until March

Through a wash of crackles, static and time comes a stern, almost manic Germanic voice proclaiming “I am Doctor Brahms.” This is the starting point for the British Library’s ongoing exhibition celebrating 140 years of recorded sound, which takes visitors from that early point in audio history through other technological breakthroughs, historic voices and events, right up to the modern digital age.

Audio accounts for a substantial part of the British Library’s assets and activities. It holds a large collection of historical and historic recordings in its sound archive, a vast proportion of which have been digitised with the aim of making them available online. One hundred of these feature in the 140 Years of Recorded Sound exhibition and can be listened to in four booths, or pods, placed at intervals in the display area.

Steve Cleary, lead curator of literary and creative sound recordings at the British Library and a co-curator of the exhibition, explains that the Season of Sound was conceived partly to raise the profile of the archive. “There were three reasons behind it,” he tells PSNEurope. “The first was to highlight Save Our Sounds, an ambitious project particularly related to the sound archive. With the help of Heritage Lottery funding we have been digitising analogue audio held in our collection while there was still time to do it.”

Cleary says there was some pressure to get on with this critical and necessary process before it was too late: “We will reach a point where either the analogue material degrades or the playback equipment will disappear. So we are acting now.” Save Our Sounds extends beyond the British Library collection, taking in 10 regional centres round the UK, including Manchester City Council, The Keep in Brighton and London Metropolitan Archives.

The £9.5 million received from the Heritage Lottery Fund in 2015 is being used to digitise 500,000 rare and vulnerable recordings. As part of this the British Library’s Technical Services department, which runs the Conservation Centre for transferring original sounds on to digital media, is training technicians who will in turn train other personnel in how to carry out this process.

Another aim was to show what is happening with sound recording and distribution today, rather than focusing wholly on the past. “We want to reflect the way the commercial music landscape is now with digital downloads being the medium of choice,” Cleary says. “There are now new systems available to deal with digitally released material on block. This depends on working with the record companies, big and small. It’s a full time job because there is no legal requirement for people to deposit audio with us, as there is for books.”

The third reason, Cleary says, was to provide something “enjoyable, engaging and informative”. That intention certainly seems to have been achieved. Even on a rainy Monday evening, a healthy number of people came to the British Library’s Entrance Hall Gallery and spent time perusing the exhibits and displays. The 140 Years of Recorded Sound exhibition is arranged on the back wall, with a mixture of text, video and, naturally, audio recordings played through headphones.

Early examples include recordings made on Edison’s tin foil Phonograph, with film of a former assistant to the inventor/entrepreneur recreating the famous Mary Had a Little Lamb recording. The Phonograph also made the first wildlife recording possible. This was made by Ludwig Koch, a pioneering sound recordist specialising in natural history. Koch worked for the BBC and amassed a collection of important historical recordings. Among these was a lacquer disc copy of Brahms’ voice, as featured in the exhibition, which was originally captured on wax cylinder.

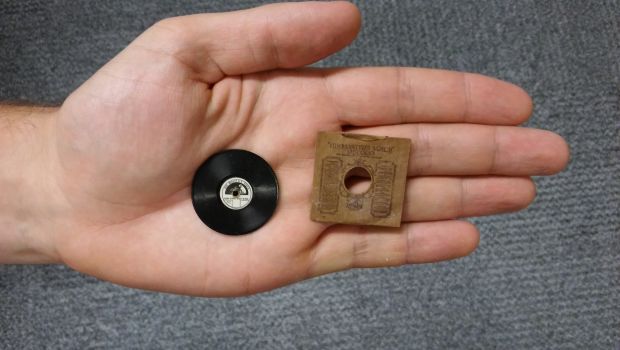

A more traditional aspect of the exhibition is the use of display cases. These contain some of the artefacts held by the Library. Included is a tiny 78rpm disc made for Queen Mary’s doll’s house in 1924.

Alongside this, from the same year, is something more scandalous: a 78 of James Joyce reading from his widely banned novel Ulysses. This is a very rare example of spoken word, being one of only two recordings made of the author. It was commissioned by Sylvia Beach, owner of the Shakespeare and Company bookshop in Paris, who published Joyce’s novel. Recorded at HMV Studios in the French capital, only 30 copies were made.

Joyce’s voice is No. 10 in the 100 Sounds from the Archive. Among other historical figures that can be heard are Florence Nightingale, King George V and Amelia Earhart. The 1932 recording of the flying ace is said to be an early example of tape-based editing. There are also music recordings, including Les Paul’s track Lover (1948), made up of multiple recordings of his guitar from acetate discs playing at different speeds.

Also featured are the earliest known recordings of computer music from 1951; the Dr Who theme, produced by Delia Derbyshire at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop; Nelson Mandela speaking at the Rivonia trial in 1964, made on a form of Dictaphone; Cracking Viscera, recorded by the modern successor to Ludwig Koch, Chris Watson (1994); and the result of last year’s EU referendum. The most recent clip is also from 2016, a rap track by the Swet Shop Boys entitled T5.

In all there are approximately seven hours of audio to be heard. Cleary says the exhibition puts a different twist on the traditional museum experience: “Usually audio and video are subordinate to the main event but we wanted to reverse that and focus on sound and listening,” he comments. “In other exhibitions the idea is to keep people moving but for this they are invited to sit down and spend time taking everything in.”

Among the artefacts of interest to professional audio visitors are a 1971 Nagra IV-S, which, as Will Prentice, head of the library’s technical services agrees, is not just a key piece of equipment and engineering but also a beautiful thing in its own right. Alongside this is another Nagra recorder, the SN miniature from 1970.

A featured part of the exhibition is an installation by musician Aleks Kolkowski. This is based on the wireless log kept by 16-year old radio fan Alfred Taylor, who, in 1922, bought a receiver and aerial with a £200 (approximately £8,000 today) prize from a newspaper. This exhibit features radio sets of the times, clips of programmes and Alfred’s meticulously kept note book, detailing what he picked up from stations such as 2LO (which would become the BBC’s London service), 2ZY in Manchester and PCGG from The Hague.

Live events also feature, including the Radiophonic Workshop playing live and Chris Watson in conversation with David Attenborough. More are planned for 2018, with Brian Eno in conversation among the highlights.

The Season of Sound continues until March.

www.bl.uk

Source: mi-pro.co.uk