Malcolm Young: A Tribute to AC/DC's Solid-As-a-Rock Rhythm Guitarist

The rhythm guitar playing of Malcolm Young is one of rock’s great monuments. A massive edifice—solid and weighty, yet hewn with brutally exacting precision—it was the cornerstone of AC/DC’s music from the Seventies right up to our own time. Many rank Young as the greatest rock rhythm guitarist ever, which puts him out front in a distinguished company that includes icons like John Lennon, Keith Richards and all who have followed in their wake.

Rhythm guitar is an often-underrated art, but it was far from Young’s only contribution to the AC/DC juggernaut. He was also the band’s founder and one of its chief songwriters, working in both cases in tandem with his younger brother and AC/DC lead guitarist Angus Young. In 2014, AC/DC vocalist Brian Johnson summed up Malcolm Young’s importance to the band as follows:

“He was the one that was behind AC/DC. He was our spiritual leader. He was our spitfire.”

It was indeed a sad day for rock and roll, as Eddie Van Halen tweeted, when that flame was extinguished on November 18, 2017, particularly as Malcolm’s passing came just a month after the death of his and Angus’ elder brother George Young, who had played a key role in AC/DC’s career. But Malcolm’s death was far from unexpected. Rock fans all knew that his health was poor. He’d suffered from lung cancer, heart trouble and dementia. The latter affliction had forced him to leave AC/DC in 2014 and go into managed care.

That sad departure marked the end of an adventure that had begun in 1973, when Angus and Malcolm first formed AC/DC in Sydney, Australia. The brothers were born in Scotland but had emigrated Down Under in 1963 with their family. It was a major, and sometimes difficult, transition for two young boys. Angus once recalled coming home and saying, “Mum, I think they put us on another planet.”

But that only served to strengthen the bond between Angus, Malcolm and George, as well as their eldest brother Stephen and sole sister Margaret. (There were two other brothers, William Jr., who came to Australia with the family, and Alex, who remained behind in the U.K.) One of the major ways in which that bond was expressed was through music.

“Among all my brothers, we all played instruments,” Angus told me in 2014. “We could all play a party and try to cover all the different styles of music. Because some liked a bit of folk or jazz, some liked blues, other ones wanted rock.”

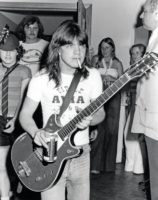

Rock would turn out to be the family business. George was the first sibling to find fame, with the mid-Sixties beat group the Easybeats, which he’d formed with a fellow migrant, Harry Vanda. It was Vanda who gave Malcolm the guitar that would be his signature ax for the entirety of his career, a 1963 Gretsch Jet Firebird that he’d modify extensively over the years.

“It was Harry’s guitar,” Malcolm told me in 1995. “He gave it to me when I was 14, just as a gift. He’d played it for a while, but he’d moved on to Gibsons. He knew I was keen and he threw it my way. And I just adapted it for rhythm—with a fuzz box in the early days. You know, a kid in the bedroom—just stripping it apart for rhythm. It evolved out of necessity, that guitar.”

Malcolm and Angus even played with George and Harry in a group called the Marcus Hook Roll Band for a short while. This was right before Angus and Malcolm got AC/DC going, taking that band’s name from an electrical voltage indicator on Margaret’s sewing machine. Even at this early stage of the game, the siblings’ guitar roles were already pretty much locked in.

“Angus always just played lead,” Malcolm told me. “He never bothered with chords. He just wanted to solo. And I used to sit there figuring out tunes—the chords and what have you. I was playing guitar since I was about four. So I’d be strumming along to a little Elvis riff or whatever. And of course when the Beatles came out, I was around ten, 11 or 12; I was trying to learn their tunes, with the chords. Angus played at an early age as well. But by the time he got to be like ten or 11, it was Hendrix and things like that. So he was already hearing the guitar in a different way than me. Sometimes he’d say, ‘Mal, you should play leads as well.’ But I just felt so uncomfortable with it. So I said, ‘The band’s rockin’. Let’s just keep things as they are.’ All we wanted to do was make a noise, to be honest with you.”

Rhythm guitarists often double as a rock band’s lead singer/front person. But Malcolm never fancied that role. From the moment Angus first wore his schoolboy suit onstage—another idea suggested by sister Margaret—he was destined to become the brother who grabbed the attention of the crowd, frequently upstaging each of the band’s three vocalists: Dave Evans, Bon Scott and Brian Johnson. And while Malcolm would step out front to nail the occasional backing vocal, his place was generally the backline. From there he drove the band like a locomotive—albeit one with a lot of heart.

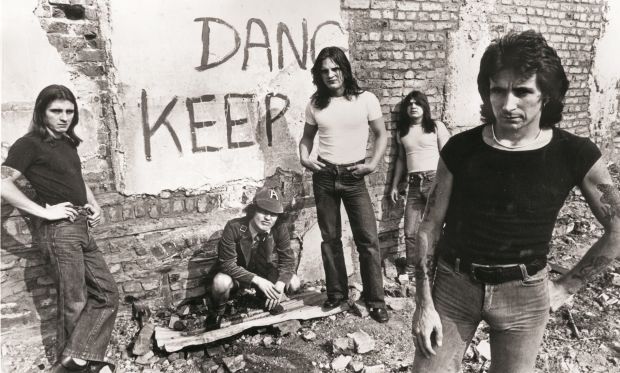

While AC/DC went through three drummers and two bassists over the course of their career, the band’s groove never sounded like anything other than AC/DC. That strutting, swaggering backbeat, that randy, rhythmic push-and-pull—that’s what Malcolm Young gave to rock. And it’s one of the things that defined AC/DC, from their 1976 debut album, High Voltage, onward.

“You do have to hit the guitar pretty hard to get that thing from it,” Malcolm once explained to me. “But it’s not just a smash smash. It’s a dig. You actually dig into those strings. You’re gettin’ under them! It’s percussion, is what it is. It’s rhythm. I think of it more like piano playing sometimes. It’s what I know—all I know. And it suits me right down to the ground.” Young’s rhythm guitar mastery is ultimately a matter of that unquantifiable factor known as feel, although Fender heavy picks and heavy gauge strings—often Gibson Sonomatics, .012–.056—also contributed the nasty bark of his tone.

“That came about by accident, really,” he said of the heavy gauges. “Just to keep the band in tune! With two guitars, thumpin’ the Christ out of ’em at the same time, nothing ever sounded like it was in tune. But it came with a sound, these thick strings.”

Factor in vintage Marshall amps, and heavy is the key word here. But Malcolm never considered AC/DC a heavy metal band, although they were sometimes described as one. Then again, they also initially were classified as a punk band, largely because their mid-Seventies emergence coincided with the dawn of punk rock and they seemed a bit bratty and working class.

“We were giving punk music a good name,” Angus once quipped. “Because that was the word they’d use to describe us—punk band. They’d get the wrong idea. They’d put us on the same bill as punk bands. And they sure got a shock when they started spitting at us and we spat back.”

Malcolm preferred to describe AC/DC simply as rock and roll, once stating that AC/DC and the Rolling Stones were the only real rock and roll bands left. And while their career hasn’t lasted quite as long as the Stones, AC/DC have survived the vicissitudes of changing rock fashion and setbacks that might have defeated a lesser band. Malcolm is credited with holding AC/DC together when singer Bon Scott died in 1980, keeping Angus focused on writing the songs that became Back in Black, hailed by many as AC/DC’s greatest album. They got the songs down first, then they went out and found the voice that would bring them to life. The nasty, high-pitched screech that Brian Johnson could produce with his vocal cords seemed an anatomical impossibility. But it was the perfect voice for AC/DC’s rough-and-ready brand of rock and roll.

Songcraft was another one of Malcolm’s priorities and strong suits throughout AC/DC’s career. He’d often fine-tune riffs and ideas that Angus brought to the table, building songs that grab you from the first note and keep your head banging right through to the very end.

“We play with dynamics a lot in this band, through the years,” Malcolm explained to me. “Just being a straight-ahead four-piece band, you’re very limited. So we’ve got to use a lot of dynamics. It’s all about suspense and drama.”

Malcolm’s personal life wasn’t devoid of drama either. In 1988 he had to take time off, missing the majority AC/DC’s Blow Up Your Video U.S. tour to get his alcoholism under control. This was the first occasion on which he was replaced by his and Angus’ cousin Stevie Young—another family member with the right DNA and many hours of jamming with Malcolm and Angus under his belt. But Malcolm was soon sober and back on the job, spearheading AC/DC through their 1990 “comeback” album, The Razors Edge, a latter-day classic.

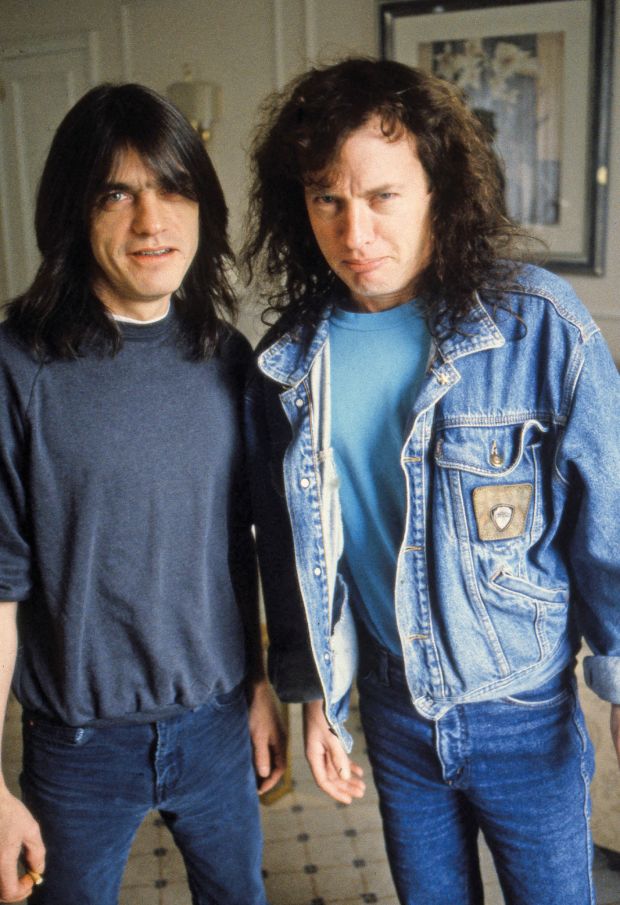

Over the years AC/DC worked with many legendary producers. Along with the stalwart team of George Young and Harry Vanda, there was Mutt Lange, Bruce Fairbairn, Brendan O’Brien and Rick Rubin—a virtual who’s-who of top rock producers. But Malcolm was always the ultimate authority for Angus, when it came to guitar parts.

“No matter who we did work with,” Angus told me. “I always looked to Mal in the end if I played a guitar solo or a little break here and there. And he would always say yea or nay.”

Malcolm and Angus’ guitar playing is so closely interwoven that it’s difficult to consider either one in isolation. This is also what’s quintessentially rock and roll about AC/DC. They’re heirs to the two-guitar tradition of John Lennon and George Harrison, or Keith Richards and any of his co-guitarists in the Rolling Stones. Only Malcolm and Angus’ sibling connection made the mesh even tighter.

“If you’ve been jammin’ since you were kids together, I guess it becomes second nature,” Malcolm said. “We know each other so well. Any brothers. If you can imagine two brothers, they know each other inside out. It’s virtually the same with guitar playing.”

Given the brothers’ close fraternal bond, Angus was among the first to detect the early signs of Malcolm’s dementia—the confusion and memory problems that are part of the condition. But the closeness made these distressing symptoms all the harder to accept. In 2014, Angus told me that Malcolm’s symptoms had been growing for “a number of years. He got a little disconnected when we were making the album Black Ice. It was becoming more and more kind of noticeable. But I’ve also noticed over the years, in hindsight, that he was having problems. But it was hard to figure out what it was, strange enough as it seems.”

Dementia usually strikes people much older than Malcolm was at the time, and there are also many specific forms of dementia. These factors made it difficult for the Young family to obtain a definitive diagnosis at first.

“We were kind of hoping that Malcolm would get better,” said Angus. “We kind of delayed on that, not knowing. I suppose it is a kind of hard thing. I mean he’s still there. But the condition itself, you know that it’s not him. I know his wife kind of feels that way. It’s like she’s lost her husband.”

Malcolm was also diagnosed with lung cancer shortly after the Black Ice tour. Surgery to remove the cancer was successful, but the ordeal must surely have weakened him further. He also suffered from a heart condition which required that he wear a pacemaker. The Twenty-teens were a bleak time for AC/DC in general. In 2016 severe hearing loss forced Brian Johnson to leave the band.

But even in Malcolm’s absence from AC/DC, his presence was still felt. Much of the band’s most recent album, Rock or Bust, was pieced together from unfinished song ideas that Malcolm had left behind. And this is most likely how it will be in the years to come. While Malcolm Young has left his body, his influence and his contribution to rock music will continue to loom large.

“Malcolm’s always been a strong presence in the band,” said Angus. “He formed the band. It was his brainwaves that put it all together. It was him who guided us from the beginning.”

Source: www.guitarworld.com