“There’s nothing wrong with finding an old church pew and making an instrument out of it”: Rick Kelly of Carmine Street Guitars

Guitar fanatics go loopy for well-aged timber with a backstory. Contemplate, then, the sound of a guitar made from wood salvaged from the fire-damaged steeple of a church built in 1790, that had the bells’ vibrations ringing through it for more than two centuries.

A native New Yorker, Rick Kelly of Carmine Street Guitars has been building guitars since the 1970s, and for the past couple of decades he’s been able to lay claim to being arguably the most New York of the many luthiers based in the Big Apple. Thanks to the stuff that goes into his instruments, Kelly’s guitars are quite literally made from New York. What might seem a gimmick in other hands, though – if an extremely compelling one – came entirely naturally to Kelly, and of necessity, as he eked out the starving artist’s subsistence in the early days of his career.

“I was born in Jamaica Hospital in Queens in 1950,” Kelly tells us. “I had made my first instrument in high school, it was a little ukulele, and then when I went to college at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore in 1968, I was running out of money, so I started making Appalachian dulcimers to sell at craft shows in upstate New York. I made a living doing that for about 10 years, until the late 70s, when I started making more solidbody electric guitars.

“That’s where I learned about how old instruments sound better than new instruments, and the kind of wood Stradivarius used in his violins. And then I lived on a farm out in rural Maryland and I cut firewood,” he adds. “I had wood heat in the house for ten years, so I learned so much more about wood from chopping wood four hours a day to keep my shop and the house warm, that it was a real backbone to where I am today.”

The bones of old New York

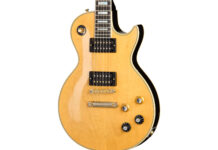

Although Kelly has built all kinds of guitars in his more than four decades at the workbench, he has become known for his Tele-style instruments in particular, some of which are slightly modified, while others aim pretty close to the original template. As for the wood, though, Kelly’s guitars adhere more closely to the very first pre-production Fenders.

“Look at Leo Fender’s first prototypes,” Kelly says. “They were made out of pine, what I’m doing now. But the wood was just lumberyard pine, he wasn’t using old-growth, so it was probably a good idea to get rid of it.”

The stuff Kelly’s using, on the other hand, is old-growth in the extreme. Wood used in his Bowery Pine Series – named for the section of southern Manhattan from where much of has been salvaged – has been reclaimed from the demolition and refurbishment sites of some of New York City’s oldest buildings. Kelly calls it ‘the bones of old New York,’ and in many cases it’s timber that was known, in a previous age, as ‘the King’s pine’.

In the 1750s, some two decades before the United States declared independence, the entire region of the Northeastern Colonies was considered crown land, and King George I claimed exclusive rights to all of the pines in New England and upstate New York. His emissaries marked the best and tallest of these Eastern white pines with an emblem called The King’s Broad Arrow, declaring them property of the King of England, for the exclusive use of the Royal British Navy. While the vast majority of such trees are long gone, hikers in more remote stretches of these forests will still occasionally come across one of the King’s Pines, displaying its faded Broad Arrow.

Later, pines that escaped the axe prior to the founding of the United States were often barged down the Hudson River from the massive virgin forests of the Adirondacks in upstate New York. And although their use in buildings in Manhattan and Brooklyn in the late 1700s and early 1800s would seem to date them fairly precisely, consider that these tall pines might already have been hundreds of years old even before their harvesting.

While it might seem the perfect angle for a guitar maker in this tonewood-conscious age, this knack for salvaging wood came to Kelly early on, and out of necessity.

“I majored in sculpture in college,” Kelly says, “and struggling through that I had to source wood that was already reclaimed to make my sculpture, because I was making things out of wood even then. And that’s what led me to the instrument world around the same time, and knowing why old instruments sound better, because the wood now has gone through this ‘mystery of the molecules’, as I like to call it. The resin in the wood crystallises and opens up the pores for vibrations, and then the vibrations that travel through the wood have changed it for so long, and the fact that the wood has seasoned so much and becomes so resonant with age. I knew right then that there was a lot to that.

“Through that, I learned that there’s nothing wrong with finding an old church pew and making an instrument out of it; it’s going to sound amazing. So, sourcing the old wood is something that goes way back to the earliest part of my career, originally more out of desperation, but it wound up to be the thing that I do the most, that makes the most difference in my guitars compared to other people’s guitars.”

From bells to barrooms

One of Kelly’s first notable reclamations included some wood from the 150-year-old NYC loft apartment of filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, a friend and client of Kelly’s. Distinguished sources have included the famous rockstar haunt, the Chelsea Hotel, historic NYC bars such as Chumley’s Speakeasy and McGurk’s Suicide Hall, and several other storied locations (handrails and fixtures of which might also turn up old-growth rock maple used in necks, and other woods). When asked to pick a few notables from the stack, though, Kelly definitely has his favourites.

“Probably top of the list would be Trinity Church,” Kelly offers, “the oldest surviving church in New York, built in 1790. And it came from the freakin’ bell tower, so the bells were ringing on this wood for 200 years. I treat it like it’s blessed, because it is.

“Also, some of the wood I got from the roof of the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral up on 26th Street, after a fire burnt the roof off. That wood was extremely gorgeous and special to me. The heat of that fire was 1,000 degrees, and it was put out quick enough to save the whole interior of each beam. I went up there to get the wood on Memorial Day, and there’s a cop car there that I had an encounter with, and I tell the cop, ‘The Monseigneur gave me permission to take this wood.’ He actually bought it and let us take a few beams, but oh, what a waste. There were so many good beams in there.”

Given the link between beer-soaked dives and the electric guitar, many of the city’s infamous drinking establishments have made fitting reclamation sites, too.

“Some other great wood came from Chumley’s Speakeasy over in Bedford Street, one of the oldest speakeasies. That’s where the term ‘you’re eighty-sixed’ comes from [meaning you’ve been barred from entry], because it’s at 86 Bedford Street. That building got renovated, and I got three truckloads of wood out of there in the pouring rain; I had to buy all the workers lunch. It was from 1822, even older than the building I’m in now, so these old buildings and the timbers inside them… what they’ve seen go by. They were trees when George Washington was president.”

In addition to insisting that you can hear all that experience in the wood – the bell tower beams, for example, having had a 200-year head start on those pores reforming sympathetically to the musical vibrations that so many guitarists and luthiers likewise swear by –Kelly derives immense pleasure simply from working with the material.

“It’s amazing working with this stuff, sitting and playing with it all day,” he says. “When I cut the Chumley’s wood, because it was an old bar for so long, the wood got so beer-soaked, and that smell when you walk by a bar in the morning, it comes wafting out the window from the night before? That’s what this wood smelled like when you cut into it. It had picked up those odours, because it’s a porous material. It stays in there.”

Up the neck

Another aspect of the craft that Kelly has learned from older instruments, and which he has found to have been proven elsewhere, is the use of a big neck. When the customer will allow it, Kelly favours a chunky neck profile with substantial depth, and he’s convinced that this benefits both instrument and player in multiple ways.

“Not only does it sound better,” he relates, “because there’s more wood in the instrument so it has more tone that way, but it actually relaxes your hand more, too. We have a few hand surgeons here in the city who are also guitar players, and that was their prescription for patients that would come in with hand injuries from playing guitar – there’s a lot of carpel-tunnel injuries, and stress in the elbow – they said ‘Try a bigger neck!’ And I can’t tell you how many times people have been able to play again because of the bigger neck.”

While the prescription might seem counter-intuitive – our instinctive feeling often being, ‘My hand hurts, so reaching around a fatter neck will only hurt it more’ – Kelly and others have discovered that the added wood and a full, deep profile tend to support the hand and ease playing, rather than inducing strain:

“It fills your whole hand. You’re not pinching and squeezing making a chord. And that’s where you build up the stress in your hand, the thin little bones and muscles that run through your hand and up into your forearm.”

As for the sonic component, Kelly also believes that the size of the neck and the wood used in it are responsible for a larger proportion of any guitar’s tone than is generally credited by most players.

“I think it’s probably closer to 60/40 in favour of the neck,” he says. “People would never give the neck that much credit, but I know in my instruments when I don’t use a truss-rod and I make them out of pine, I feel I get that kind of result.

“People gasp when they hear ‘no truss-rod in a pine neck!’ [a feature in some, but certainly not all, of Kelly’s guitars], but when you use a certain kind of wood and a certain part of the wood that’s as old as this is – and it grew much slower back in the 1700s when these trees were alive, and then they lived to full maturity – you can make a complete neck out of that without a truss-rod, and it doesn’t move. They’re going on 20 years and they still haven’t moved at all. It’s just a wonderful thing.”

Carmine Street calling

Parallel to the wood he works with, Kelly has also found his New York City location conducive to the craft and contemplation of musical instrument making, as much for the artists who have wandered into his shop over the years – and often wandered out as friends – as for the history of the specific address itself.

Kelly moved into his premises on this short street in west Greenwich Village in 1990 and has worked there ever since, accompanied in recent years by his apprentice and assistant Cindy Hulej, now a skilled and respected guitar-maker in her own right who continues to share the shop space.

“It’s so weird,” says Kelly, “I was looking for a store, and I found this place. It kind of drew me to it. And I never even knew this until I moved onto this block, but later on I found out – on this little street called Carmine Street – not only was Jose Rubio, Tom Hoff, Tom Humphrey, Lucien Barnes, Michael Gurian, they all built guitars on this block, and it only runs three blocks long.

“Now my shop’s on this block, and it was totally coincidental. Martin Guitars was right around the corner, too. They had their first shop there in the 1800s right on Hudson Street, before they moved out to Nazareth, Pennsylvania. It was considered that they shouldn’t be allowed to be in the Woodworker’s Union, so they just said, ‘Alright, we’ll go out where the other Germans are.’”

Right from the beginning, it seems this little Carmine Street joint was a haunt for notable NYC guitarists, as well as those from further afield. Many became devoted clients, and several are legends who are no longer with us.

“I thought it was special knowing Chris Whitley when he was alive here,” says Kelly, “and almost most of all, Robert Quine was a good friend of mine. He played with the Voidoids, and with Lou Reed for many years. He was one of my best friends. He’d come to the shop every single day when he was in town; what an incredible guitar player.

“And Lou Reed himself… he was a great guitarist at the end there, and he was using them Battery Pines too. Allen Woody when he came to town with the Allman Brothers Band or Gov’t Mule, I’d go over to see them at the Wetlands or CBGBs, and he’d bring me on the tour bus, and everyone was smoking pot. I miss a lot of those guys.

“And I met Keith Richards once when he was in the shop. He said he was in ‘guitar heaven.’ And one time, Lou was here with Dave Stewart from the Eurythmics, and I didn’t have a camera – so a lot of it’s up in the head, the memories. Bob Quine, Patti Smith, and Lou Reed all hanging in the back here and talking, and I didn’t have a recorder going. The stories went on for two hours… and it was just amazing.”

Carmine Street Guitars was recently the subject of a documentary movie. Visit carminestreetguitarsfilm.com to find out more.

The post “There’s nothing wrong with finding an old church pew and making an instrument out of it”: Rick Kelly of Carmine Street Guitars appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

Source: www.guitar-bass.net