Guitarist's Guide to Playing Bass: 20 Tips to Help You Think Like a Bassist

Bass is more than just a guitar with two fewer strings. It has a different tone, scale length, feel and musical role, and in many cases it requires a different conceptual and technical approach. Guitarists who are new to playing bass will often double the guitar part one octave lower. There is certainly a place octave doubling — just listen to Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion,” Led Zeppelin’s “The Ocean” and Pantera’s “I’m Broken.” But there is so much more that can be done with the bass guitar.

Bass is more than just a guitar with two fewer strings. It has a different tone, scale length, feel and musical role, and in many cases it requires a different conceptual and technical approach.

Guitarists who are new to playing bass will often double the guitar part one octave lower. There is certainly a place for lockstep octave doubling—just listen to Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion,” Led Zeppelin’s “The Ocean” and Pantera’s “I’m Broken.”

But there is so much more that can be done with the bass guitar.

As a bassist who later took up guitar, I have developed 20 general guidelines that I live by when I play the bass. Apply them to the instrument, and hear your playing improve as they help you to think and play like a real bass guitarist.

1. PLAY FOR THE SONG

More often than not, solid bass playing requires that you exercise restraint and subtlety rather than showcase your technique and slick moves. In many situations, it’s best to work mostly with the root notes of the chords and lock in with the drummer’s kick and snare drums.

2. LEARN TO WALK

“Walking bass” originated in jazz and blues, but it has since been adopted in other styles. The term refers to a way of playing in which the bass line remains in perpetual motion as opposed to staying on or reiterating one note. The line “walks” from one chord’s root note up or down to the next, mostly in a quarter-note rhythm, with the occasional embellishment.

To achieve this, you use “transition notes” to smoothly connect the dots and bridge the gap between different root notes as the chords change. The transition notes can be any combination of chord tones (arpeggios), scale tones that relate to the chords, or chromatic passing tones.

In general, chord tones are the musically safest bet, as they sound harmonically consonant, while scale tones add a touch of light dissonance when heard against an underlying chord. The more chromatic notes that are used, the more dissonant the line becomes, as these notes momentarily clash with the prevailing chord. Whether this is a good thing or not is up to your discretion and instincts.

FIGURE 1 shows a stock blues walking bass line. Although the line is rhythmically animated, with staccato (short, clipped) swing eighth notes and a triplet fill at the end of each bar, it is fairly tame harmonically, as it uses mostly chord tones (the root, fifth and dominant seventh) with a brief chromatic run-up to the fifth.

By contrast, FIGURE 2 illustrates a jazz-style walking bass line played over these same two chords for which chromatic passing tones are liberally employed. Note the difference in contour between these two examples, the first being very angular and the second being smooth and rolling. Also note the use of “dead” notes (indicated by Xs in the notation), which help propel the line. These are performed by picking the string while lightly muting it with the fret hand.

When crafting a walking bass line, it’s best to land on the root note whenever there’s a chord change. If you’re staying on the same chord for several bars, it’s a good idea to play the root on the downbeat of every other bar or every fourth bar, depending on how grounded you want the line to sound.

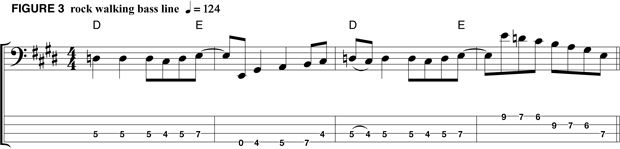

The walking bass concept isn’t just for swing grooves and can be also employed with great results in a rock context with an even-eighths feel. Inspired by Herbie Flowers’ tasteful bass work on David Bowie’s 1974 hit, “Rebel Rebel,” FIGURE 3 is a fairly straightforward example of a great way to use scalar passing tones and fills to spice up a bass line over a repeating two-chord progression.

3. LOCK IN WITH THE DRUMMER

In a rhythm section, part of the bass guitar’s role is to function as a liaison between the drums and the rest of the band. In most cases you want to make the bass and drums sound like one entity, and a great way to do this is to craft bass lines that fit like a glove with the drummer’s kick and snare drums. Using octave root notes is often an excellent way to do this, the low octave corresponding to the kick drum and the high octave hitting with the snare, typically on beats two and four, which are also known as the backbeats.

Octaves allow you to create an active bass line with an interesting, angular melodic contour without clashing harmonically with the underlying chords, as the octave root note “agrees” perfectly with the chord.

“Grooving” doesn’t necessarily mean playing the same thing over and over. John Paul Jones’ playing throughout Led Zeppelin’s “The Lemon Song” is a perfect case in point, as he embellishes the groove and stays within the bass’ role as a support instrument for six solid minutes without repeating himself once.

4. USE OCTAVES AND FIFTHS

After the octave root, the fifth is the most harmonically agreeable note you can play. Many classic bass lines have been constructed using mostly roots, octaves and fifths as the framework. The great thing about this approach is that it allows you to create a bass line that is interesting and melodic, locks in perfectly with the drums and doesn’t clash harmonically with the underlying chords. FIGURE 4 is an example of this kind of approach, inspired by John Paul Jones’ nimble playing on Led Zeppelin’s “Thank You.”

5. TONE IS IN THE HANDS

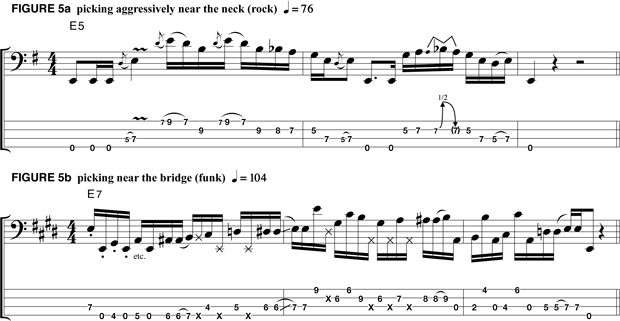

This old adage could not ring truer for bass playing. Plucking the strings hard and near the base of the fretboard (FIGURE 5a) like Black Sabbath’s Geezer Butler makes them slap against it; plucking the strings near the bridge with just the very tips of your fingers (FIGURE 5b) lets you get that punchy Jaco Pastorius/Rocco Prestia machine-gun 16th-note attack. (Be sure to check out the video demonstrations for these musical examples on GuitarWorld.com to hear the difference in tone between them.)

You can go from a dull thud to a sharp, funky punch simply by choosing where along the string you pick it and how aggressively you hit it. Between that, your pickup selector (if your bass has one) and tone controls, you have a considerable range of tonal possibilities before the signal even hits the amp.

6. TO PICK OR NOT TO PICK?

Not all bassists use their fingers to pluck the instrument. Megadeth’s David Ellefson, Rex Brown of Pantera and Down, Yes’ Chris Squire and Paul McCartney use a pick, and John Paul Jones, the Who’s John Entwistle and Michael Anthony in his Van Halen days were known for switching from fingers to pick depending on the song. If playing with a pick works for you, go for it. I recommend the large, non-celluloid kind, such as Dunlop’s Tortex Triangle, with a thick gauge (at least 1mm).

The large surface area of the big triangle picks is well suited to the wide spacing of bass strings and will help you keep a grip on the pick. Tortex (or Delrin, depending on the manufacturer) is also sturdier than celluloid and less likely to break, and the thick, unbendable gauge will allow you to get more volume and power out of those thick strings, with less effort.

7. SINGLE-FINGER TECHNIQUE

Some record producers actually prefer having bass players use a pick because the attack is more even. But if you’re a fingerstyle player and want to achieve a more consistent attack, try using only one finger, such as the index (instead of alternating between the index and middle fingers) as much as possible. John Paul Jones copped this technique from Motown bass legend James Jamerson and made great use of it on several classic Led Zeppelin tracks, such as “Good Times Bad Times” and “Ramble On.”

8. GET YOUR TIME SOLID

Someone has to keep the tempo steady, and if the drummer can’t, than the bassist has to. The pocket depends on you, so learn how to be your own metronome. Don’t just count in 4/4—you should also feel in 8/8, especially when playing ballads, where the tendency to rush the tempo is greater. To help you land on the beat more accurately, listen to the drummer’s hi-hat or ride cymbal, not just his kick and snare drums.

9. TO FILL OR NOT TO FILL?

Fills are the little pieces of ear candy that embellish a solid bass line and help propel a song. Listen to how other bass players set up a new section, and shamelessly jack anything that grabs your ear. Playing fills that conclude one section of a song (such as a verse) and lead into the next (such as the chorus) is a great way to break monotony in a bass part and set yourself apart from whatever the guitarist is doing.

Filling is an art form in and of itself, in that there’s a fine line between adding to the song or groove and obscuring it and detracting from it. In keeping with the “bass-and-drums-as-one” concept, make your fills coincide with a drummer’s so that they sound like the same person’s idea being expressed. If a drummer plays a fill, it’s usually at the end of every second, fourth or eighth bar, so listen to the drums and pick your spots to fill accordingly. Of course, all your playing decisions should depend on the style of music you’re playing, and some styles, such as hip-hop or club music, are more about maintaining a relentless groove, with very little variation.

For examples of great fills, check out R&B/soul session players such as James Jamerson (countless Motown hits), Chuck Rainey (Aretha Franklin, Steely Dan) and Nathan Watts (especially on Stevie Wonder’s “Do I Do”), or rock players such as Rex Brown, Stone Temple Pilots’ Robert DeLeo (another Jamerson disciple) and Duff McKagan of Guns N’ Roses. And don’t let genre get in the way—just because it’s a “Motown” fill doesn’t mean it can’t be used in a rock context, and vice versa.

10. OCTAVE APPROPRIATE

Are you playing in the right register (octave)? Perhaps that cool part you came up with sounds badass played down low but may be too heavy for the mood of the song. Or perhaps it’s too high and is interfering with the vocal or guitar part. Make sure your note-range choices are right for the situation.

11. AVOID LOW-B OBSESSION

If you’re playing a five-string, don’t just play sub-E notes, as it can become annoying. It’s one thing to hit a low B or C every now and then for dramatic effect and to show everyone who’s boss, but unless you’re in a Korn or Type O Negative tribute band, don’t live there.

12. SUBSTITUTE DIFFERENT CHORD TONES

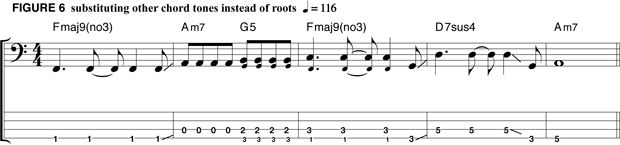

Occasionally playing the third or fifth of the underlying chord instead of its root note can radically change the whole feel of a chord progression, and when done tastefully it can add warmth or tension. This device has been used for centuries by great classical composers like Bach and Beethoven and creates what are known as chord inversions. Master pop songwriters such as Elton John and Paul McCartney use inversions, via bass line substitutions, to build their chord progressions to a harmonic climax.

Realize that the ear reckons harmony from the ground up, so as a bass player you have the power to dictate how the chord is going to sound and fundamentally change its character. FIGURE 6 is an example of a common rock chord progression for which the bass line takes a left turn (in bars 2 and 3) to create chord inversions. In the second and third bars, instead of playing the roots (shown in cue-size notes and tab numbers), the third or fifth of the chord are substituted, creating a continually ascending and more melodic bass line in the process.

13. GREASE

It’s that grimy, funky stuff that oozes between the beats. With all due respect to hardcore prog-rock bands, for which precision is key, rock and roll has always been more about attitude and spirit.

This isn’t an excuse to be sloppy and unmusical, but more an exhortation to make low, rumbling noises and revel in it. Listen to John Paul Jones’ low-end grumble during the “Hey baby, oh baby, pretty baby” chorus section of Zeppelin’s “Black Dog” (played with a pick) or Black Sabbath’s Geezer Butler on pretty much any song. For a more modern take, check out session legend Pino Palladino’s work on D’Angelo’s Voodoo album. In some situations, it’s perfectly okay to make excessive fret noise, be a little behind the beat or slide out of a note perhaps a bit longer than you should, as long as it’s not disruptive to the music and contributes to the intended vibe.

14. SHAKE IT

I’m not talking about a long trill or extreme vibrato but literally shaking a pitch. Fret the note, pick it, then quickly slide, hammer on or pull off to another fret and back, as demonstrated in FIGURE 7. Regardless of what style you’re playing, the resulting sound is funky and adds a little extra kick to the sound of the rhythm section. Sure, guitarists can do this too, but it just doesn’t sound the same (or as good) on that little instrument.

15. USE DEAD NOTES AND RAKES

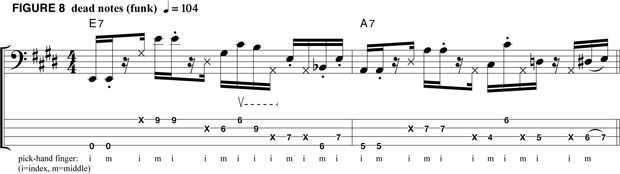

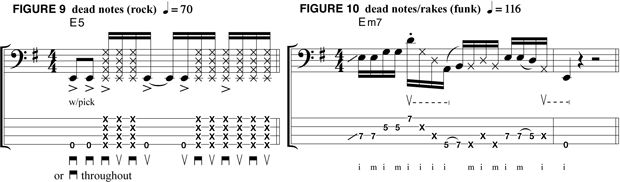

Just as you might mute the strings on your guitar with your fretting hand while you strum “chucka-chucka,” the same principle and function applies to bass, whether it’s funk (FIGURE 8) or hard rock (FIGURE 9). Rakes on a bass are executed a bit differently than on guitar: you perform them by dragging a picking finger across the strings in an upstroke, usually in a specified rhythm, as demonstrated in FIGURE 10.

16. ARTICULATION VARIATION

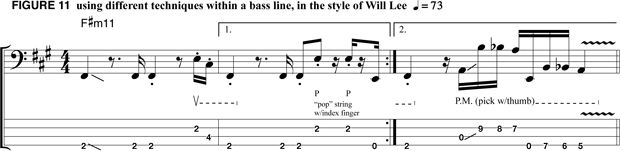

As a guitarist, you employ all sorts of techniques to convey your musical statements, and you can do that on bass, too. Check out session legend Will Lee’s work in Dionne Warwick’s “Déjà Vu.” Lee makes use of rakes, palm muting while picking with his thumb, slapping, and finger slides in addition to plain-old conventional fingerstyle playing (FIGURE 11). And he does it without ever interrupting the groove or getting in the way of the vocal.

17. IT’S ALL BASS

A cool bass part is a cool bass part, regardless of what instrument it was played on, be it electric bass, synth or piano, so be open to hearing new ideas. Next time you’re at that bar and hear house or club music blasting over the sound system, listen to the bass lines. No matter how far-flung it is from your preferred musical style, you can translate it to your own bass playing.

18. LESS IS MORE

Take “September,” one of Earth, Wind & Fire’s most enduring tunes. Bassist Verdine White is capable of playing so much more, but in this song his bass line is almost rudimentary. Even so, it’s funky as hell, making great use of rests and staccato phrasing—space between notes—and, without fail, people get up and move as soon as that bass line kicks in. For a more modern example, listen to Branden Campbell of Neon Trees. His lines never get more complicated than eighth notes with the rare fill, but his fat tone and solid playing more than adequately complement drummer Elaine Bradley’s grooves and help propel the songs.

19. MORE IS MORE

A master groove monster like Juan Nelson from Ben Harper’s band can lull you into a groove, then hit you with a fill like the one heard at 4:30 in “Faded,” from The Will to Live album. The groove and lick shown in FIGURE 12 draws its inspiration from this approach.

20. LET IT ALL HANG OUT

What do you want people to hear in your playing? Anger? Joy? Whatever it is, get in that zone and play it like you mean it. Whether you’re a shredder or a “feel” player, express yourself. Because if you’re not connecting with people, what’s the point?

Source: www.guitarworld.com